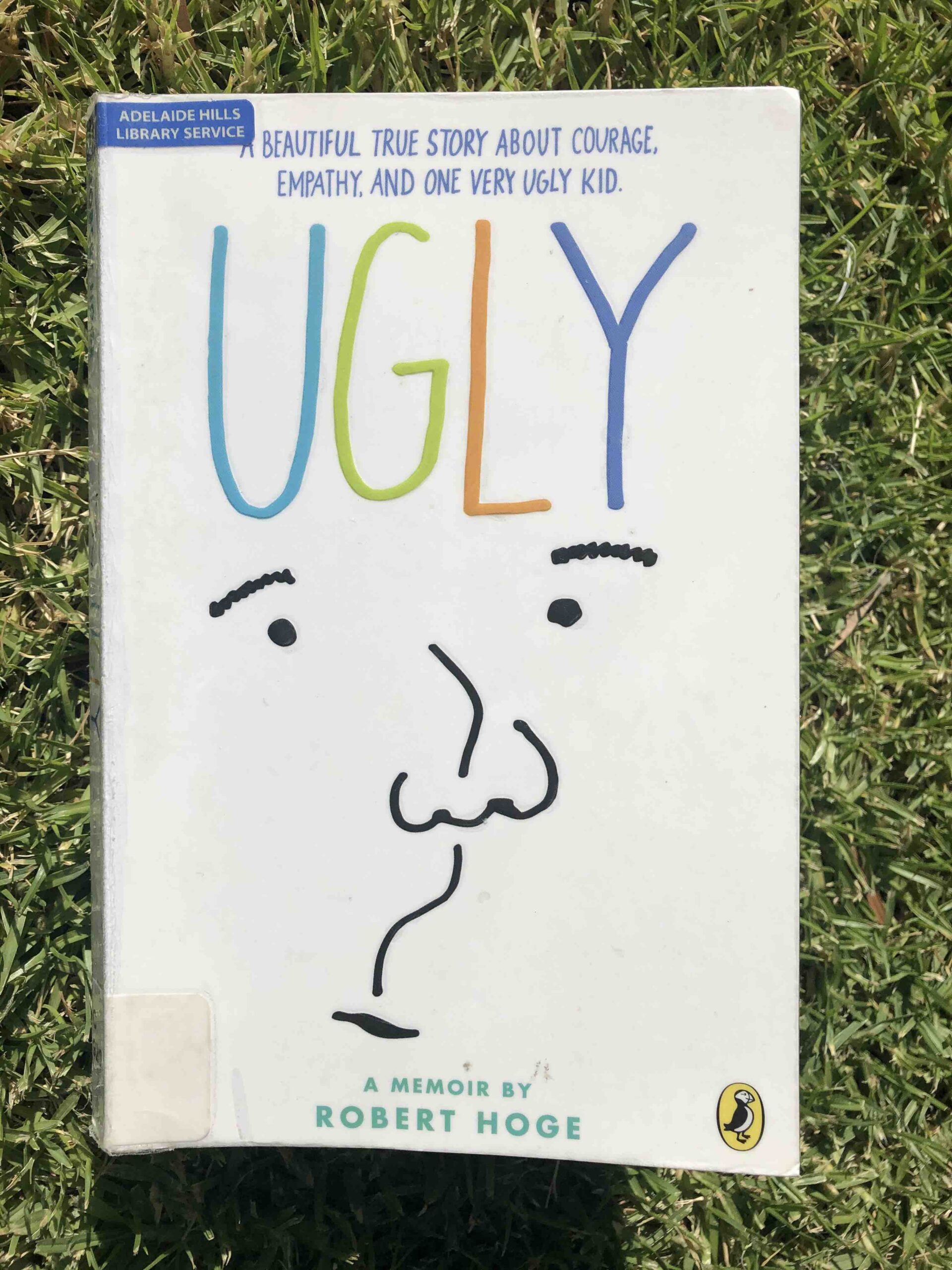

‘Ugly’ is a memoir by Robert Hoge about his childhood in Australia from his birth up to the age of 14 years of age. Robert’s story is a genuine, but at times harrowing, account of his experience of living with facial difference and physical disabilities. This review focusses on the version for younger readers aged eight and above, but there is also a book for adults. ‘Ugly’ is a great book to use in the classroom context to introduce issues relating to disability such as inclusion, discrimination and unconscious bias. Some teachers mistakenly believe that ignoring disability will result in their students not seeing disability or not developing prejudiced or stereotyped ideas about disability. While non-disabled and disabled students are far more alike than different, and this should be highlighted, ignoring difference can lead to harmful misconceptions and missed opportunities for inclusion and social change. Reading a book such as ‘Ugly’ opens up a conversation about diversity and respectful interactions.

‘Ugly’ is sometimes compared with ‘Wonder’, a best-selling American novel by R.J. Palacio about a child named Auggie who is also living with facial difference. ‘Wonder’ is better known than its Australian counterpart, presumably because in 2017 it was made into a movie starring Julia Roberts and Owen Wilson. However, ‘Ugly’ has significant advantages over ‘Wonder’, primarily because Robert is writing about his lived experience. R.J. Palacio probed into unknown territory by relying solely on her imagination to write about this topic. At the time of writing, she had never met anyone with facial difference. There is an unspoken rule in the disability community- before you create fictitious disabled people, get to know real ones. It is too easy to trivialise, misrepresent or stereotype disabled people. The way disabled people are represented in novels matters. Or better yet, leave stories about disability to those with lived experience. No amount of research can ever equate to lived experience and perspective.

Lived experience, that means direct experience of disability, is very important to the disability community. Lived experience of disability means that you have first- hand experience of disability rather than understanding specific disability perspectives from education or proximity to disability. Only someone with lived experience can tell you what it is like to walk in their shoes, to live with their disability and to experience disability-related barriers to social justice. Understanding disability, through teaching or allied health, is not lived experience, it is professional experience. The two should never be confused. Amplifying disabled voices is also important to the disability community. Consequentially, introducing your students to a book such as ‘Ugly’ which provides a first-hand perspective of disability, can help further the message of inclusion. But what is ‘Ugly’ about?

The story begins with how Robert sharing how he was born with a tumour across his face:

…..jutted out from the top of my forehead and ran all the way down to the tip of where my nose should have been. It was almost twice the size of my newborn fist. It had formed early during my development and made a mess of my face, pushing my eyes to either side of my head. Like a fish. (pp 4-5)

Robert also had physical disabilities due to his ‘mangled’ legs, resulting in the need for prosthetic limbs:

The right leg was only three-quarters as long as it should have been and had a small foot bent forward at a very strange angle. The foot had four toes, and two of them were partially joined together. My left leg was even shorter and only had two toes. Both looked bent and broken. (p. 5)

Robert described his mother’s ‘pain and grief’ at giving birth to a ‘little monster’. The word ‘monster’ is confrontational, highly charged and provocative as it leads us to acknowledge that disability slurs are used against disabled people. In this scenario, as in others throughout the book, Robert utilises understatement to outline, rather than explicitly describe terrible events. It took Robert’s mother one week to see her son, who was in intensive care. Robert used his mother’s words from her diary to describe her reaction:

‘I didn’t feel anything for this baby’, she wrote in her diary. ‘I had shut off completely. I had made up my mind I was not taking him home’.

She packed her bags and left the hospital without me. (p.10)

Robert’s mother eventually decided to bring her son home, and she provided a loving, supportive home afterwards. However, it’s worth noting that disabled students reading this book may find it traumatic to read about parental rejection based on disability. The narrative of disabled people being a burden is a pervasive one in our society and must be countered at all costs. It would be helpful for students to be navigated through this part of the novel with a clear understanding that disabled people are valued members of our society and our schools.

One of the most disconcerting parts of the novel was Robert’s work experience in a Catholic high school. He described assisting in a classroom for a week, and it appeared to go smoothly until he was summoned to the principal’s office on the last day. The principal was a well-spoken, middle-aged woman and the encounter that followed was incredibly disturbing:

‘It would have been appropriate,’ she said, without a hello, ‘if we were warned before you came.’I had no idea what she was talking about.

‘Warned?’ I asked.

‘Yes, warned’, she said. She raised her voice slightly, like I was a kid in grade two. ‘About you.’

‘About me?’

‘When you arrived on Monday, we had to quickly swap the class you’d be in. You were supposed to work with the grade-two teacher.’I wondered for a second whether kids in grade two would be tested on how to spell the plural of ‘potato’. My next thought was that until we’d arrived, we were just names on a piece of paper anyway, so it couldn’t have been that hard to change. Then it dawned on me what she meant. She was talking about the way I looked. (pp. 188-189)

Robert described how he cried and apologised for his appearance, and the principal responded with the single word, ‘Good’, as she dismissed the pain she had caused. While other instances of bullying occurred throughout the novel, these were by children whose immaturity and lack of understanding provides some explanation for their behaviour. However, in this situation, it was an adult in a position of authority, trust and respect. Principals hold the highest level of authority within the school by virtue of their position. There was an enormous imbalance of power misused by the principal to harm and bully a child. There is another hierarchy here- that of a non-disabled person rejecting and shaming a disabled person’s identity. This section of the novel will require support and guidance for students who have had traumatic or negative experiences with adults; however, it is also an excellent opportunity to reflect on power dynamics and student voice.

In the final chapter of ‘Ugly’, fourteen-year-old Robert is faced with the decision of whether to go ahead with another serious operation to improve his appearance. This time Robert’s parents allowed him to decide for himself rather than making the decision on his behalf as they did in the past. He carefully considered the high risks involved with this operation, including losing his vision and even death. Robert thought about the pain and distress of previous surgery and decided not to go ahead. Instead, he decided to own his face. He reclaimed a sense of worth and pride, along with a constructive acceptance of his disability. I highly recommend this book.

More Resources

Ted Talk ‘Own Your Face’

Teacher Notes

https://www.hachette.com.au/content/resources/9780733634338-teachers-notes.pdf

Robert Hoge Website

An interview with Robert Hoge