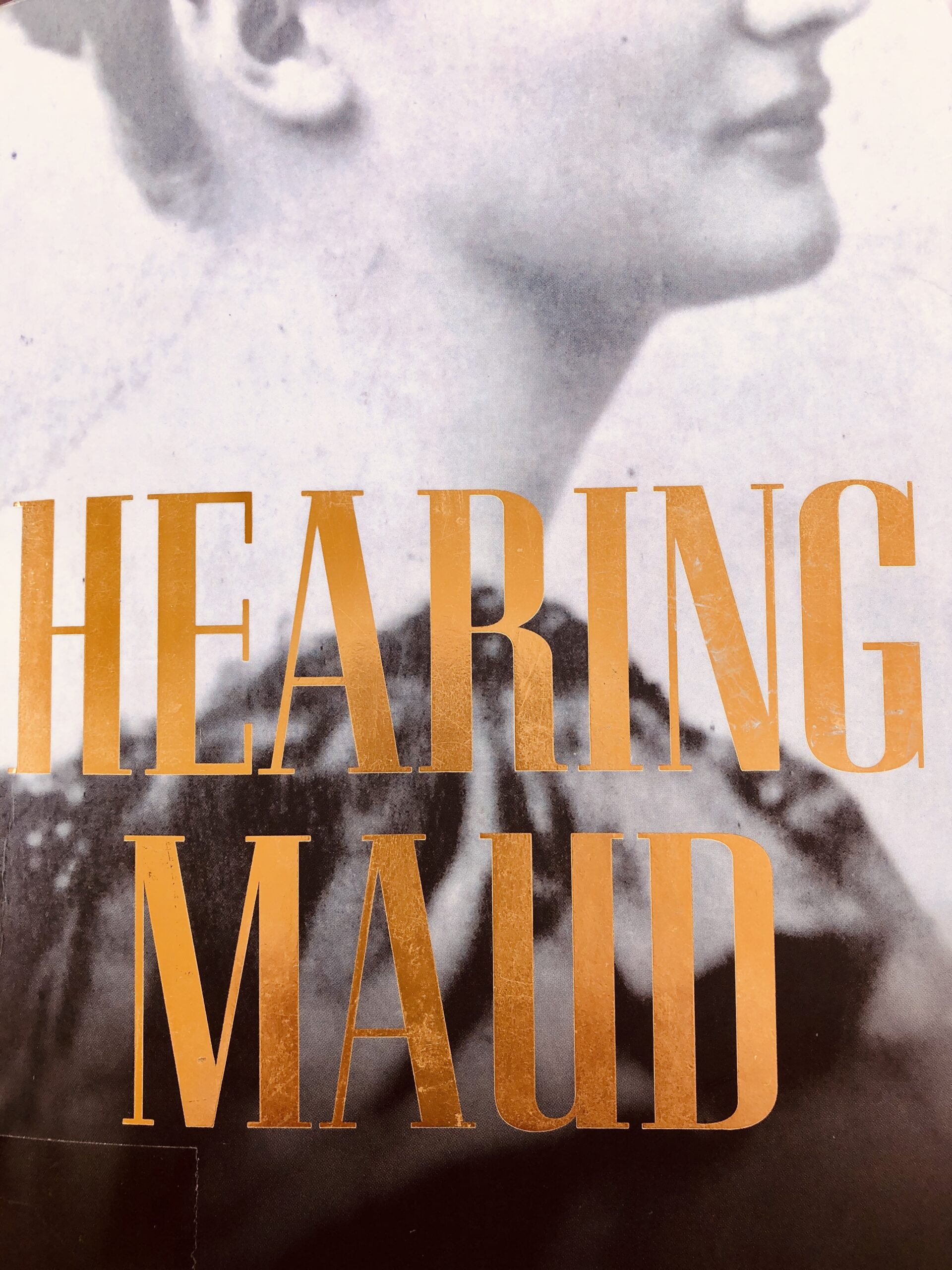

Author: Jessica White

Publisher: UWA Publishing

Year: 2019

Themes: deafness, sign language, speech, presume competence, disability, family and resilience

‘Hearing Maud’ is a brilliant hybrid work of personal memoir and biography by Jessica White. It is told through the lens of deaf studies. It recounts the author’s experience of deafness at the age of four from meningitis and growing up in the 1980s in an Australian rural farming community. Jessica’s lived experience is interwoven with the story of Maud Praed’s life, a woman who was profoundly deaf from birth, who lived one hundred years earlier. Parallels are drawn between the lives of Jessica and Maud as they are forced to negotiate their way in a hearing world by communicating through speech, rather than sign language, a mode difficult for those who are deaf. In the juxtaposition of these two life stories, discriminatory attitudes toward deafness, and the privileging of speech are tracked over time. And while there has been progress, there is still a long way to go. Jessica states:

Born one hundred and four years after Maud, I’ve learned the attitudes to deafness that corralled her life still enclose mine. But there is a crucial difference: she helped me to recognise them, and to escape. (p. 143)

‘Hearing Maud’ outlines the devastating psychological impact of assimilating into the dominant culture where speech is preferred. For Jessica, this resulted in isolation, loneliness and exhaustion from the demands placed upon her to succeed. In her teenage years, she experienced an eating disorder. Maud was on the periphery of society throughout her life, developed a mental illness and was institutionalised in an asylum, where she stayed until she died almost forty years later. The themes within this book have broader application to other disabled people who have invisible disabilities, feel intrinsically inferior to the norm or have difficulties with communication.

As someone who is hard-of-hearing, this book resonated with my own experience. In particular, the notion of being caught between two worlds, not identifying with the deaf community, and not fitting in with the hearing world either. Jessica’s description of her growing self-awareness of her disability during a session with a psychologist matches my experience:

Within seconds I realised that a huge amount of my daily anxiety came from my expectation that I act as a hearing person. Constantly checking body language, listening for cues in conversations so I knew when to respond, straining to hear and lip-reading, were all mechanisms that I relied upon heavily to pass as a hearing person, instead of simply explaining that I was deaf and asking people to speak more clearly. No wonder I was always so tired; the constant vigilance was exhausting. Not only that, but I blamed myself for failing to interact with others as smoothly as someone with all their hearing. (p. 194)

Every teacher should read this book. It will provide an understanding of the lived experience of deafness. As well, it outlines the importance of Auslan, the debates regarding cochlear implants and eugenics, and explains how the advent of Darwinism dissuaded educators from teaching sign language (speech was, and still is, considered a signifier of intelligence and a means of distinguishing the higher cognitive ability of humans from animals). There are ramifications of Darwinism today in our education system. For example, I am a teacher of students with disability, many of whom use Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) rather than speech, yet there is enormous pressure placed on students to speak, even when it is difficult for them. Speech is considered a priority and is often viewed as a superior form of communication, yet there is little reflection on why this belief exists. And the belief that learning to speak should take precedence within an education context is incorrect. There is no hierarchy of communication and there are many effective forms of communication, including Auslan, that are not based on speech.

‘Hearing Maud’ is a work of creative non-fiction with the purpose to entertain. It is not a textbook, and Jessica White does not explain her usage of the term ‘deaf’. Deafness (with a lower case ‘d’ to refer to the physical condition of not hearing), when viewed through the medical model of disability can be portrayed as a deficit, a burden and a personal tragedy. Yet, when deafness is viewed through a social model, the environment creates the disability. Therefore, changes made to the environment (e.g. providing visual cues and sign language) and policy (translators provided for everyone and sign language taught as a second language at school), could potentially alleviate barriers to inclusion and deafness would be considered another aspect of human diversity. However, the Deaf Community (with a capitalised D to indicate Deafness as a culture), who are a smaller group within the larger group of people with the physical condition of not hearing, view deafness as a culture and consider themselves a linguistic minority who communicate through sign language. Whilst they believe that the social and physical environment should be adapted for deafness, they go one step further than the social model of disability. The Deaf subculture rejects the notion that deafness is a disability and have therefore rejected membership of the disability community (Harvey 2013). They wish to preserve their language and therefore oppose cochlear implants, which encourage people to rely on auditory channels, and inclusion in the educational system, as this means linguistic exclusion from sign language (Brennan 2003). Yet, paradoxically they claim the benefits that have been secured by them from the disability community (Harvey 2013).

I highly recommend Hearing Maud for adults. For those interested in literature on disability, Jessica White has created an online resource called ‘Writing Disability in Australia’. This resource aggregates writing on disability in AustLit into a searchable index, with the aim of drawing attention to the ways in which Australian writers have represented disability. It highlights the significant and imaginative achievements of writers with disability, the structures and assumptions of ableism, the resourcefulness with which people with disability navigate their everyday lives, and the ways in which disability lends itself to creativity, lateral thinking, and resilience.

You can find ‘Writing Disability in Australia’ here.

References

Brennan, M. (2003) Deafness, Disability and Inclusion: The Gap between Rhetoric and Practice in Policy Futures in Education Vol. 1 No. 4

Harvey, E.R. (2013) Deafness: A Disability or Difference in Health Law and Policy Brief Vol. 2 Issue 1 Article 6

You can sign up to read our blog and hear about our monthly webinars by clicking here.